The Trouble With 300

In his memoir Always Cedar Point, the park’s long-time Vice President and General Manager John Hildebrandt recalled, “What Dick wanted was a ride that would surpass Magnum but would carry the same genetic code: steel structure, tubular steel track, no inversions, high capacity, world class stats: highest, steepest, fastest.”

B&M, he said, was never considered, as at that time, as their three models (standing, inverted, and sit-down) all focused on compact layouts packed with inversions. (Kinzel couldn’t have known that B&M was actually in development of its first airtime-filled, inversion-free hypercoasters – Apollo’s Chariot at Busch Gardens Williamsburg and Raging Bull at Six Flags Great America – that would both debut in 1999. Of course, even if B&M had been contacted, their calendar was already full with six coasters debuting in 2000. Welcome to the Coaster Wars!)

As Coaster101’s fantastic history of the ride that became Millennium Force tells it, the first response to Cedar Fair’s request for proposals was from D. H. Morgan Manufacturing – a California-based firm started in 1983 by the son of Arrow’s founder.

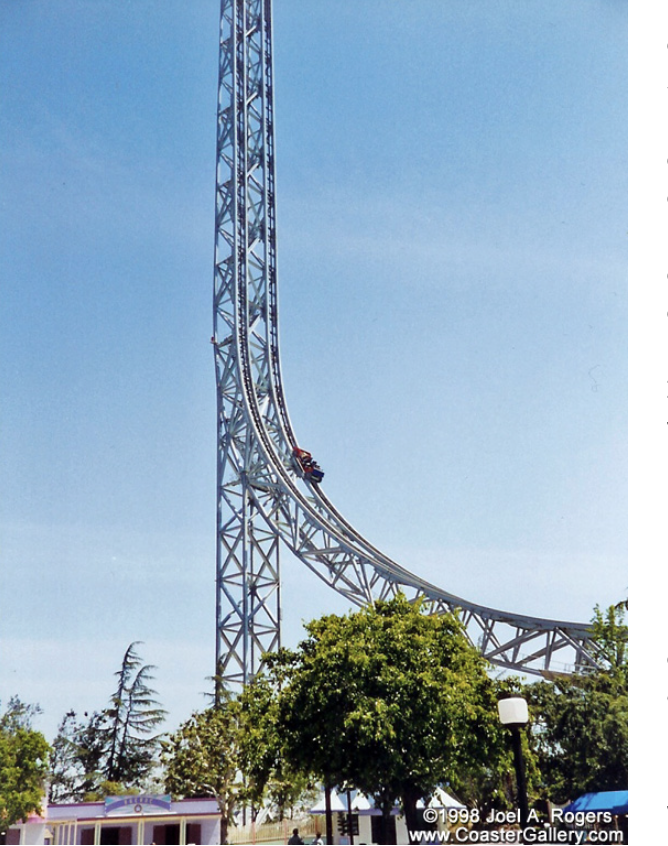

Morgan’s Arrow-like coasters had come through for Cedar Fair before, including three hypercoasters (Valleyfair’s Wild Thing, Dorney Park’s Steel Force [above], and Worlds of Fun’s Mamba, built between 1996 and 1998, respectively). So it made sense that Morgan was a shoe-in for breaking through the 300-foot ceiling at Cedar Point…

Of course, it wouldn’t be easy. A 300-foot Morgan would test a park’s space and riders’ time. Think about it: Magnum’s 30°-ascent lift hill covers a horizontal distance of just over 400 feet to reach its 205 foot height, and takes 90 seconds to reach the summit. The prospect of a coaster adding an additional 100+ feet of vertical lift would mean a lift hill that takes up tremendous real estate, uses a whole lot more steel, multiplies the stress on a chain, and drastically lowers the ride’s capacity.

It was possible, but it wouldn’t necessarily be pretty. As Hildebrandt tells it, Morgan’s as-good-as-it-gets offer was “basically a done deal” until a black horse entered the race.

Intamin

In the churning cauldron of stew that many amusement parks became in the Coaster Wars, there’s no doubt that B&M coasters were the potatoes – hearty, trusty, reliable, and even comforting. Whether stand-up, inverted, sitting, or hyper (or, into the 2000s, dive or flying or wing or…), these coasters rolled out across the industry as attention-grabbing headliners that were big, flashy, thrilling, marketable, and – most importantly – sure bets. (Today, B&M is sometimes criticized by coaster aficianados for gradually skewing toward general appeal over innovation; for being too agreeable, with less intensity in each subsequent installation as its rides become giant, floaty, and unaggressive.)

That’s significantly different from the firm that’s often cited as their counterpart: INTAMIN Rides. It makes sense. Though Intamin’s first installation dates back to 1979 (ironically, Cedar Point’s Junior Gemini – a 19-foot tall kiddie coaster next to the previous year’s record-breaking 100-footer), bolstered by the Coaster Wars, the manufacturer found its niche in the mid-90s.

Intamin’s first real headliner of the era, for example, was Six Flags Magic Mountain’s Superman: The Escape (left). Playing with prototype launch technologies and extreme statistics that saw the ride’s opening delayed by a whole year (also an Intamin signature), the ride used cutting edge linear synchronous motor (LSM) electromagnetic technologies to send riders screaming down a launch track at 100 miles per hour, pulling up into a vertical climb, and suspending weightless before falling backwards in a high-speed return to the station.

Over the late ’90s, Intamin gradually phased out the nondescript family coaster models it had supplied for decades and began to become a serious player in the arms supplying of the Coaster Wars… the manufacturer most willing to push the boundaries in pursuit of unique, record-breaking experiences that could plus parks with brochure-ready rides.

From their own sleek hypercoasters (1999 & 2000’s two Superman: Ride of Steel installations at Six Flags Darien Lake and Six Flags America) to 1998’s much-duplicated launching Impulse coaster with twisted vertical spires, Intamin attractions had all the modern smoothness of B&M, but with a fiery, feisty twist; the spiced meat of the stew, if you will, introducing launch technologies, shuttle coasters, and extreme statistics that reliable B&M wouldn’t touch.

Perhaps the best example of all things ’90s Intamin would be the Lost Legend: VOLCANO – The Blast Coaster at then-Paramount’s Kings Dominion – the world’s first launched, inverted coaster, exploding riders vertically out of a fire-belching mountain… and of course, a ride plagued by downtime, with a season-delayed opening itself, years of half-loaded trains, decades of tumultuous operations, and finally, a 2018 removal after just two decades of life.

Long story short, Intamin came out the gate as just the kind of bold, experimental manufacturer whose dabbling in prototype technologies could both combat B&M’s widely-appealing new thrill concepts and be a complement to them in the most ambitious of parks. (That kind of remains Intamin’s niche: technology-fueled, cutting-edge, and often-temperamental rides up to and including the headlining additions of Hagrid’s seven-launch, switch-track, freefall-drop Motorbike Adventure and the ultra-compact, multi-inversion, multi-launch Jurassic World VelociCoaster.)

So even as the public roiled with rumors of a 10-inversion B&M coaster coming to Cedar Point as their next big thing, with the benefit of hindsight, it’s easy to see that – at this pivotal moment at the height of the Coaster Wars – there could be no other way to go than up, no where but Cedar Point to make it happen, and no one but Intamin to make it real.

Preparation Y2K

Allegedly, Intamin was the only other ride manufacturer besides Morgan to respond to Cedar Fair’s 300-foot coaster request… And in addition to undercutting Morgan’s quoted price by “several million dollars,” Intamin was willing to pack the coaster of the new millennium with fittingly 21st century technology.

According to Tim O’Brien’s aforementioned biography of him, Kinzel recalled that Intamin’s proposal checked two boxes that Morgan’s couldn’t: “how to get the cars to the top of the 300 foot summit quickly and how to come up with a more durable material for the wheels.”

For the former, Intamin’s giga would solve the problem with what you might call the firm’s signature “innovative risk.” In this case – increasing the ride’s lift hill from a 30° to 45°. It may not seem like much, but the steeper ascent would allow Intamin’s ride to reach the 300-foot peak in a smaller footprint than Magnum’s 200-foot summit. Though such a proposal might suggest adding even further stress to the ride’s chain lift, that was the other secret ingredient in Intamin’s plan: its giga coaster wouldn’t use a chain lift at all. Instead, Intamin’s ride would use an equally-tested technology – albeit, one that hadn’t been used in this way before: an elevator lift cable.

On a standard roller coaster’s lift hill, a continuous chain is pulled through a metal trough in the track’s center, driven by a motor. When a train engages with the lift hill, a fixture attached to the bottom of each train called a chain dog folds down until it ker-klunks into a slot on the chain, drawing the train up the hill. The click click click click riders hear are one-way-folding, anti-rollback latches that – if the chain were to disengage – would keep the train from plummeting backwards. At the hill’s peak, the chain rolls over a gear and returns back to the base of the lift. There, the lift dog is disengaged, allowing gravity to take over as the train rolls down the drop.

But on Intamin’s giga, a multi-wheeled catch car attached to an elevator cable would physically lock onto the train’s underbelly while riders are loading. Then, with the same flywheel technologies that power any office building’s elevator, that cable would swiftly, smoothly draw the train directly out of the station, briskly pull it up the lift, guide the train right over the top, then be lowered back into the station to grab the next train. Voila!

Whereas a standard lift hill can generally travel 7 feet per second, Intamin’s cable lift could move trains at 22 feet per second, essentially whisking guests to the 310 foot height of the ride in under 25 seconds.

Intamin’s proposed layout would be a modified out-and-back, creating a T shaped ride with the coaster’s station and lift hill neatly fit between Lake Erie and the park’s existing Frontier Trail midway, with a bulk of the ride taking place on a small island encircled by the park’s Paddlewheel Excursions boat ride. Only the park’s Ferris Wheel would need relocated to make way for the coaster’s final turn and brakes.

According to Coaster101, Morgan reviewed Intamin’s design, and countered that their proposed ride layout would have “way too much energy coming into the station” and that their designers would need to “just put a bunch of brakes to scrub it off.” Regardless, Cedar Fair selected Intamin’s design, committing $25 million to the construction of the first ever 300-foot tall full-circuit coaster.

With rumors running rampant and discussion boards alight with possibilities, on July 2, 1999, Cedar Fair officially filed a trademark for the name… MILLENNIUM FORCE. A week later, blazing blue Intamin track began to arrive at the park… but no one was quite sure what, exactly, Cedar Point’s 21st century coaster would be…

Then, on July 22, 1999, it became official: Millennium Force would debut in 2000 as the world’s tallest full-circuit coaster. At 6,565 feet, it would also rank among the longest roller coasters on Earth, with record-breaking gravity-driven speeds of 93 miles per hour. – just one of the ten world records it touted being a part of.

But in keeping with Kinzel’s experience with Magnum, more importantly, the park that had introduced the world’s first 100- and 200-foot tall coasters would now, unthinkably, just a decade later, shatter the 300-foot height barrier. Millennium Force would be the world’s first and only gigacoaster, forever cementing Cedar Point as the gravitational center of the Coaster Wars and “The Roller Coaster Capital of the World.”

Ready to go for a ride?

Add new comment