Right at the intersection of art and science resides the roller coaster…

And though we’ve devoted in-depth features to many – from Son of Beast to the Big Bad Wolf; Expedition Everest to Top Thrill Dragster; Space Mountain: De la Terre à la Lune to Volcano: The Blast Coaster – in the opinion of many of the industry’s most devoted fans, the ride that most magnificently combines art and science in one is MILLENNIUM FORCE, the landmark gigacoaster at Cedar Point.

Rising 300 feet over Ohio’s Lake Erie, Millennium Force is the crown jewel of the “Roller Coaster Capital of the World”; the end-all-be-all of the ’90s “Coaster Wars”; the “Best Steel Coaster in the World” year after year; and true to its name, an industry pivot point perfectly bridging the gap between past, present, and future. Even having been surpassed in height, drop, speed, and length, this landmark ride is a bucket list topper for coaster enthusiasts from around the globe.

Though Cedar Point promised in 2000 that “The Future Is Riding On It,” the story of Millennium Force really is the story of the steel roller coaster and its half-century evolution… And that’s where our ride starts…

The Steel Age

You have to remember that in the grand scale of humanity’s search for amusement, the steel roller coaster is a relatively new invention. By any count, the first modern, tubular steel-tracked coaster was Disneyland’s Matterhorn Bobsleds – a 1959 addition to the then-four-year-old park. Even still, it wasn’t until the mid-’60s that “mine train” coasters began to proliferate across amusement parks; not until 1975 that Knott’s Berry Farm’s Corkscrew (left) turned upside down; not until 1978 that Cedar Point’s Gemini finally offered a drop of over 100 feet, proving that this still-new “steel coaster” medium could build taller, faster, and steeper than anyone had imagined before.

For that reason, we can’t lay the foundation for Millennium Force without acknowledging that the rise of the steel coaster began with Arrow Dynamics – a Utah-based ride manufacturer who practically dominated the industry for decades, including each of the installations mentioned above from Matterhorn to Gemini.

In fact, the story of the first three decades of the steel coaster is basically the story of Arrow: of the “mine trains” that proliferated through a generation of parks in the ’60s; of the Double Loops and Corkscrews that became standard in the ’70s; then, of the swinging suspended coasters and daunting “multi-loopers” that became mainstays of midways in the ’80s. Arrow laid the groundwork for countless innovations – and their coasters today remain the foundation of countless amusement parks across the country.

But at the intersection of the steel coaster’s rise and Arrow’s story stands one park, one ride, and one man who set the stage for Millennium Force. Cue the ’80s synths.

Magnum XL-200

Cedar Point, like many classic amusement parks, is old. Like, seriously old. Tracing its opening to the Presidency of Ulysses S. Grant just five years after the end of the Civil War, the 1870 park on Ohio’s Lake Erie began like many amusement parks did: as a lakeside bathing beach that gradually added a bathhouses, a dancehall, a bandstand, and – by 1892 – a roller coaster. (The pre-electric, gravity-powered Scenic Railway reached sensational top speeds of 10 miles per hour.) It wasn’t even until 1911 that a causeway was constructed to the island, turning the Victorian picnic park from an island to the peninsula we know today.

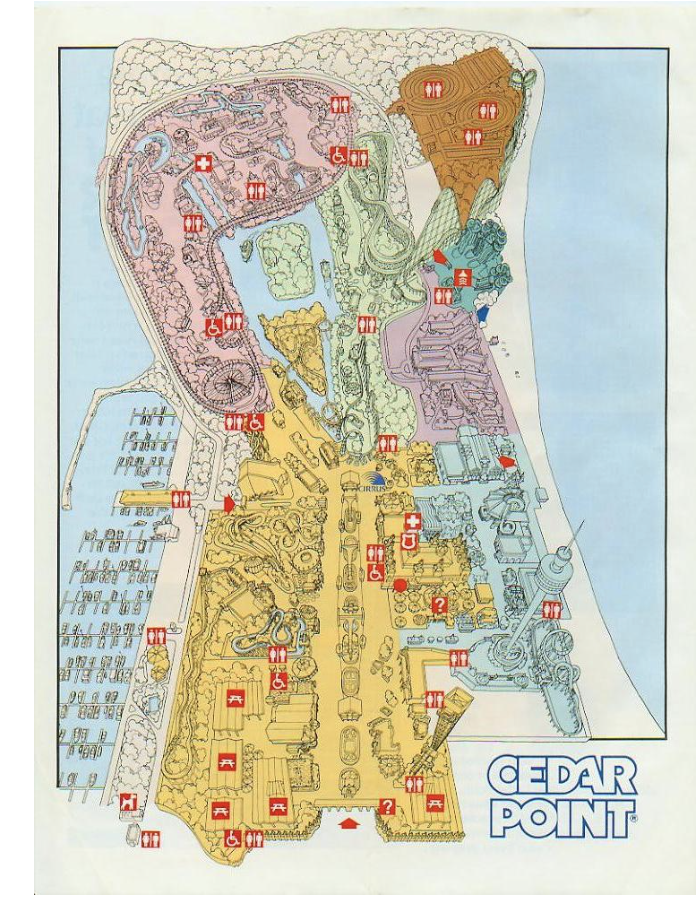

Speaking of which, to visit Cedar Point a hundred years later (left) would be to see a modern park filled with rides of its time – midways littered with log flumes, classic wooden coasters, historic hotels, and more. More to the point, though, Cedar Point was perhaps a poster child for the story of the roller coaster as told through Arrow’s innovation. The park had its dutiful ’60s mine train (1969’s Cedar Creek Mine Ride), its ’70s looper (1976’s Corkscrew), and an Arrow suspended coaster (1987’s Iron Dragon) all still reigned over by 1978’s Gemini.

But Cedar Point of the ’80s also had a secret ingredient: Dick Kinzel.

Born in nearby Toledo, Kinzel had practically been raised at Cedar Point. According to Tim O’Brien’s biography, Dick Kinzel: Roller Coaster King of Cedar Point, Kinzel began his employment with the park as a seasonal worker, then as a food service supervisor before – in 1975 – “begging” for the job of Director of Operations for the park. Kinzel was there for the groundswell of revenue surrounding the record-breaking opening of Gemini in 1978, so when he returned to Sandusky after a stint leading Valleyfair as the newly-elevated CEO of Cedar Fair in 1986, Kinzel set out to recreate that magic.

Whereas Gemini had cost a staggering $3.7 million, Kinzel now turned to the board with an almost-unthinkable request: a $7 million allowance to win back the coaster height record (which would be stolen by Six Flags Great America with 1988’s 170-foot-tall Shockwave).

“I just wanted the highest coaster in the world,” Kinzel remembered in a 2017 retrospective with the Sandusky Register, with his sights set on reaching 185 feet. But allegedly, a board member asked, “How much more would it take to get to 200?”

Magnum XL-200 opened May 6, 1989 – the world’s tallest, fastest, and steepest roller coaster… But more importantly, to Kinzel’s thinking, the first ever to top that once-thinkable 200-foot height barrier; the world’s first “hypercoaster.”

Kinzel called those “last 15 feet” the best investment in Cedar Fair’s history. “People would actually say it was worth the price of admission alone,” Kinzel said. “I honestly think it was the best decision the park ever made.” It makes sense. No coaster remains the “tallest” or “fastest” or “steepest” for long, but the first? That’s one for the record books.

Even if Magnum is, today, half the height of Cedar Point’s tallest coaster, it’s still a landmark. Its red-orange track blazes alongside the northern edge of Cedar Point’s beach, racing perpendicular to the surf in continuous, arcing airtime hills and metallic tunnels. Though today, its age betrays it (Arrow’s ramp-like hills and trim-braked turnarounds feel significantly different than the precision-calibrated, flowing airtime hills of a B&M hypercoaster, for example), there’s no question that it remains a bucket list ride for coaster enthusiasts.

Magnum is an icon not only in the park’s history, but Arrow’s. After all, in retrospect, Magnum sort of topped out Arrow’s capabilities. Though the manufacturer had literally created the modern standards of a thrill ride, the industry was standing on the precipice of a massive shift that would leave Arrow behind and introduce the designers of the 21st century…

The Coaster Wars

No one could’ve predicted in the late ’80s that everything was about to change. But right about then – just as the concrete footers of Magnum were taking shape along Cedar Point’s beach – the first domino en route to the Coaster Wars had been tapped.

It started when – in 1988 – two prominent engineers from Giovanola (a Swiss parts supplier who worked with coaster manufacturer Intamin) decided to go it alone, opening their very own engineering firm with just four employees on the payroll. Suffice it to say, Walter Bolliger and Claude Mabillard weren’t looking for work for long. Right away, they were approached by the engineering team at the recently-rebranded Six Flags Great America near Chicago with a proposal to create a next-generation version of the stand-up coaster that the duo had developed for Giovanola.

The result was 1990’s Iron Wolf – like so many B&M coasters, not the first of its kind, but the most definitive form. After all, Iron Wolf (above) debuted what would become B&M signatures, like four-abreast trains, thick-spined track, cylindrical columns, that iconic “pre-drop” dip, and precisely-engineered layouts packed with complex inversions… a substantial divergence from Arrow’s equivalent mega-loopers of the age, and certainly from TOGO stand-up coasters.

Of course, what really put B&M on the map was their return to Great America two years later with a whole new concept coaster: the inverted Batman: The Ride (above). Again, though Arrow’s suspended coasters had dangled swinging “buckets” beneath the track, B&M’s innovation had allowed for ski-lift style trains where riders – legs dangling! – were rocketed through fluid aerial manuevers and inversions.

Obviously if we jump ahead, it’s easy to see B&M’s two debut rides were the start of something substantial. The inverted coaster, in particular, became the headliner du jour of the ’90s; the must-have thrill ride that would proliferate across coaster parks, yielding wave after wave of B&M coaster designs. But especially there, at the dawn of the ’90s, the first wave of B&Ms standing alongside Arrows must’ve been like color TV supplanting black-and-white; a mind-blowing, unimaginable redefinition of what roller coasters could look like, feel like, and do.

In retrospect, it’s almost hard to imagine just how radically the amusement park industry changed between 1989 and 1999, and how quickly B&M overcome Arrow’s multi-decade reign.

Sure, Arrow would return to the “hypercoaster,” stealing the “world’s tallest” record from its own Magnum XL-200 with 1994’s Desperado, which was itself dethroned by another Arrow hypercoaster – Blackpool Pleasure Beach’s Pepsi Max Big One – just a month after. And for a while, it might’ve seemed that – just as Arrow mine trains and double loopers had become park standards in the ’60s and ’70s – Arrow hypercoasters would gradually make their way to parks across the world.

But this time was different. The rules had been rewritten, as evidenced by B&M’s own take on the 200-foot genre – 1999’s Apollo’s Chariot at Busch Gardens Williamsburg. As they’d done with the stand-up, inverted, and sitting coaster, B&M’s hypercoaster was distinctly of the next century – its precisely-designed, effortlessly weightless, high-capacity, high-reliability, and buttery-smooth out-and-back airtime hills with raised, open trains and efficient loading… such a vast divergence from Arrow’s pre-computer, herky-jerky, soldered-on-site installations.

So is it any surprise that for serious thrill parks, the ’90s was an era of unthinkable expansion. Corporate owners like Cedar Fair, Six Flags, and Paramount Parks swept across the nation, gobbling up independent parks or small-scale operators like Pac-Man. Frankly, their big-budget financial backing and corporate connections were needed to supercharge parks with a tidal wave of thrills, powered by headlining record-breakers by B&M.

The Coaster Wars had arrived. Across the industry, coaster counts exploded. The arms race accelerated through the decade, for better… and for worse.

“For worse,” for example, the reverberations of this era can still be felt in every copied-and-pasted Vekoma SLC; in every over-expanded Six Flags that can’t seem to get past decades of reliance on low-cost season passes and marketing focused exclusively on thrill-seeking teenagers; in each Cedar Fair park that boasts a dozen coasters, but zero dark rides; in the decade of recuperation each park has needed to make up for ten years without any flat rides, family attractions, or theming; in the parks that didn’t survive the era because they couldn’t muster the finances to compete with corporate-backed chains whose headline-grabbing coasters drew visitors like a fly zapper…

We say all of that to convey to you just how accelerated this era was, and how ravenously hungry operators were to turn family parks into flagships; to build taller, faster, and bigger than the competition by any means necessary, with saturated steel columns rising like redwoods among expontentially-expanding park skylines.

And “for the better,” this era of breathless expansion, intense competition, and rising new players in the industry served as a stellar alignment between Cedar Point, Dick Kinzel, and a rising ride manufacturer willing to do the unthinkable: shatter the 300-foot height record. Read on…

Add new comment