Hawaii.

1977.

In the shadow of the Mauna Kea Beach Hotel, George Lucas and Steven Spielberg build a sandcastle, each trying to think of anything but tomorrow. The former is hiding as far away as he can from the premiere of his weirdo sci-fi pet project, Star Wars. The latter is grieving in advance for his hotly anticipated Jaws follow-up, Close Encounters of the Third Kind, which the cash-strapped studio will be releasing as-is with unfinished special effects.

In respective self-defense, they talk about the day after tomorrow.

Spielberg dreams aloud about directing a James Bond movie.

Lucas counters that he has something better than James Bond.

“Are you interested?” he asks after his pitch.

With little hesitation, Spielberg says, “I want to direct it.”

With even less, “It’s yours.”

Indiana Jones is born.

Not that Indiana Smith hadn’t already been gathering dust for a while.

After the successful release his ‘50s period piece, American Graffiti, in 1973, George Lucas couldn’t shake his nostalgia. He vividly captured the sound and fuel-injected fury of his teenage years, but none of the fantasy or imagination that made him a filmmaker long before he got his license. The next project would harken back to the low-rent, high-concept spirit of ‘50s cliffhangers. He considered a rough-and-tumble adventure picture but couldn’t ignore the siren song of Flash Gordon. Though the rights holders turned him down for a direct adaptation, they couldn’t stop him from making his own soapy space opera.

In 1975, around the third draft of The Star Wars From the Adventures of Luke Starkiller, Lucas called up friend and filmmaker Philip Kaufman to talk shop about that rough-and-tumble adventure picture. Before long, they had a MacGuffin - the Ark of the Covenant - and a hero - Indiana Smith. What they didn’t have was time. Lucas wanted Kaufman to direct it, but he was already signed on for The Outlaw Josey Wales. Any consideration of directing it himself was curtailed by 20th Century-Fox giving The Star Wars the greenlight. Smith would have to wait two more years until that fateful day on the beach.

Though Indiana Jones finally existed in theory, he would get his name the following January, in a three-day marathon meeting between Lucas, Spielberg, and screenwriter Lawrence Kasdan. Across those discussions, thankfully recorded and transcribed, the three hashed out an icon and his grand debut.

Reasonably grand, at least.

With the release of 1941, Spielberg earned his third strike. Three blockbusters over budget and over schedule. It was a forgivable sin when the results broke records and saved studios, but 1941 did neither. The golden boy had finally lost some luster. Even Lucas, mastermind of the movie that speared Jaws, couldn’t get him hired. The only executive in Hollywood that took their meeting with a straight face was Michael Eisner, chairman of Paramount. He was convinced, with conditions - the pair would have to make their globe-trotting adventure for $18 million, half of 1941. Eisner knew what they were trying to do.

It was Spielberg who made the fateful comparison in the transcripts:

“What we’re doing here, really, is designing a ride at Disneyland.”

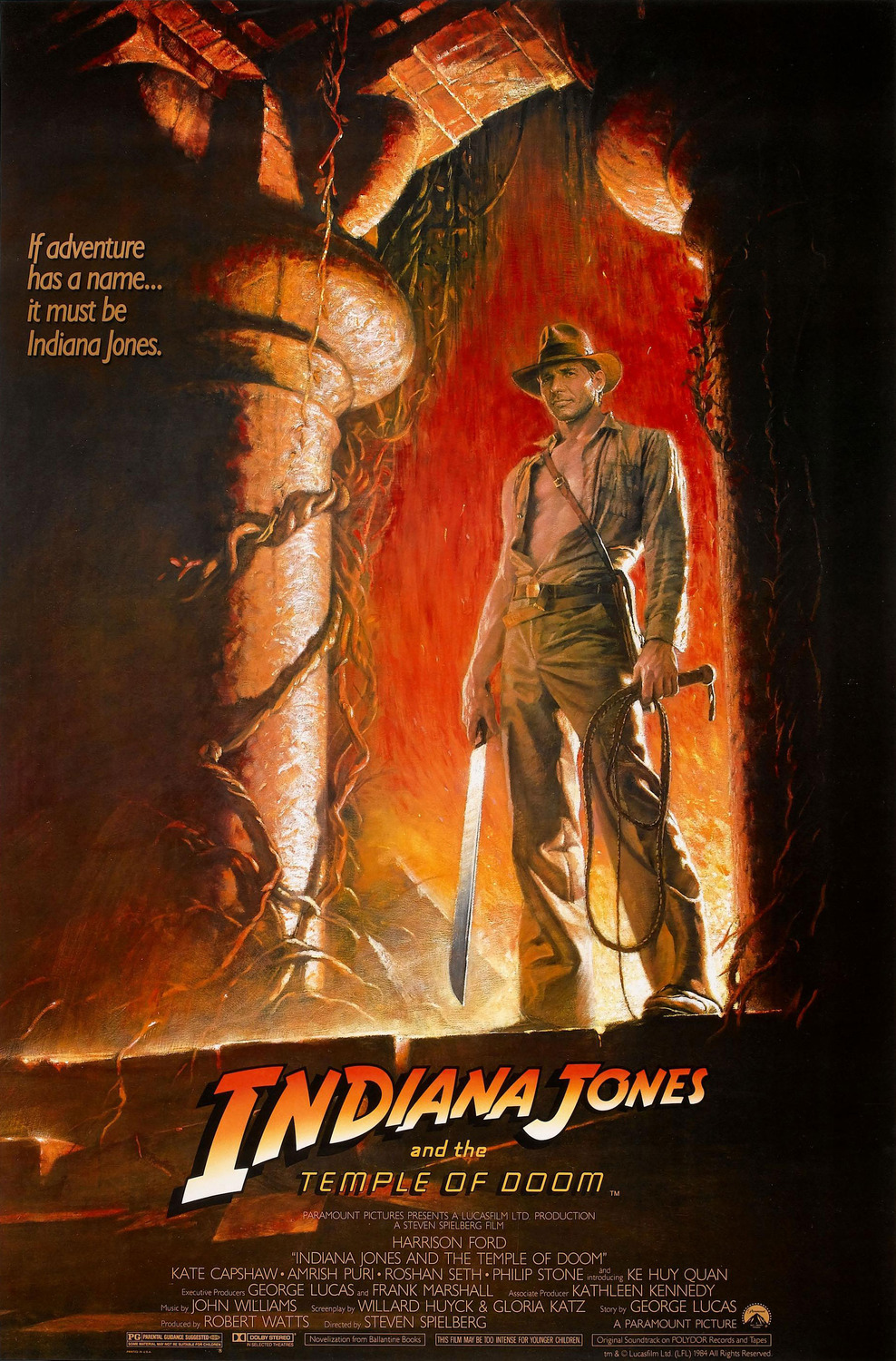

Raiders of the Lost Ark released on June 12, 1981 and quickly became the highest-grossing film of the year. In fact, it played so long, it also became the 12th highest-grossing film of 1982. The numbers cemented George Lucas as a creative force outside of that galaxy far, far away and restored Steven Spielberg’s reputation as the blockbuster king.

The numbers also promised a sequel, which was not nearly as written as Lucas had let on.

He’d assured Spielberg early that there was a trilogy already laid out in his head and the director would not need to be as involved in developing the next one. When Harrison Ford landed the role, he signed for three movies on Lucas’s word that the others were already on paper somewhere.

They were not, but with his informal retirement from directing, Lucas had time to think about them. He had time to think about a lot of things.

Tomorrowland, for instance.

“I thought that was a portion of the park that had always been a little less than what it could’ve been,” said Lucas on the Star Tours press kit. He’d lobbied Disney more than once to collaborate, but it took a fortuitous change in management to get a call back.

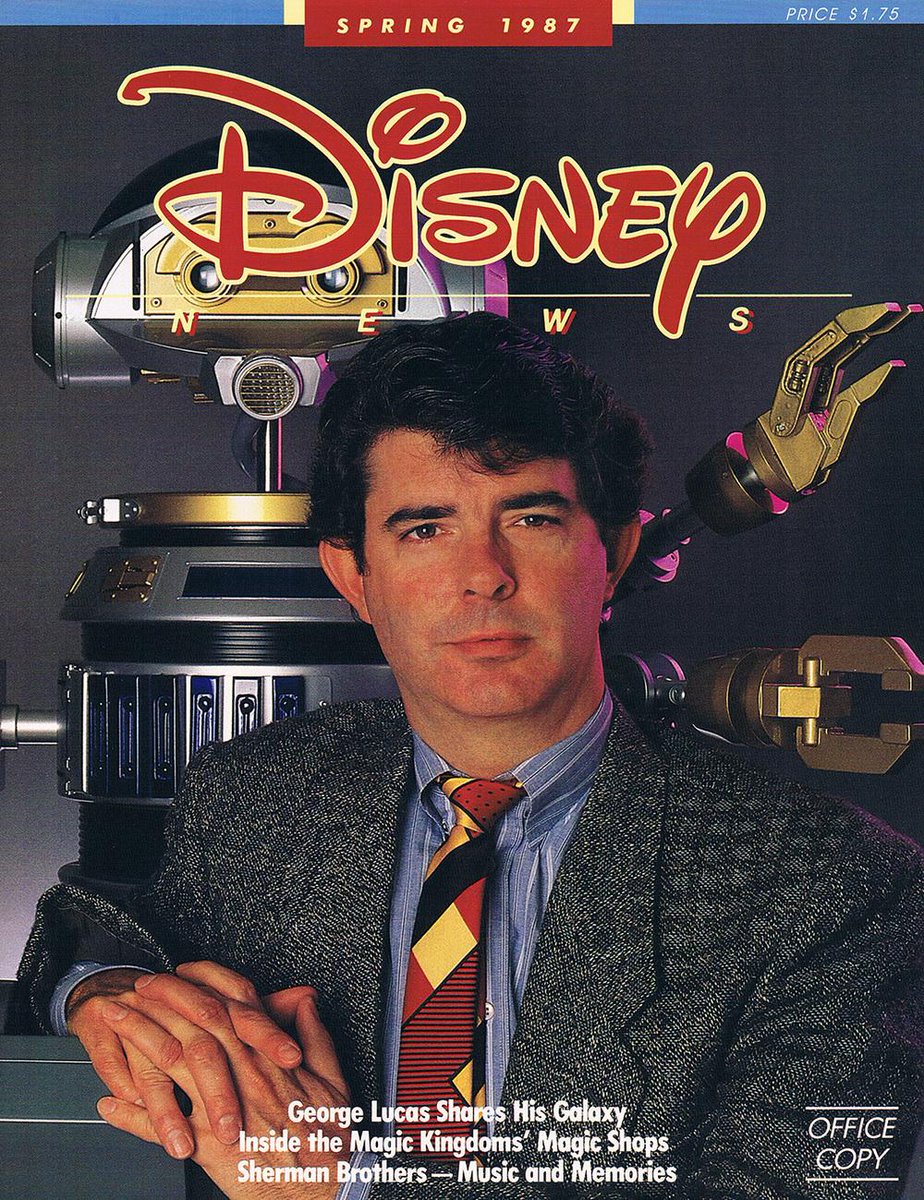

In 1984, Michael Eisner and Frank Wells took the reins of a financially precarious Walt Disney Company. They were the first CEO and president, respectively, with no relation to the name over the door. Instead, they were Hollywood, and that’s exactly what Disney needed.

Tomorrowland was a corporate problem in miniature. The last addition was Space Mountain seven years prior. It still wore the bleach-white optimism of opening day, 1955. In a post-Star Wars, post-Tron present, that particular future was looking awfully old.

One of the last major additions on the chopping block was an experimental motion simulator tie-in to The Black Hole, the studio’s disastrous Star Wars answer. During a meeting with then-president Ron Miller, Imagineer Tony Baxter humbly suggested looking beyond Disney’s science fiction catalog. Specifically, he suggested looking to Lucas and Spielberg: “These films that George Lucas and Steven Spielberg have created captivated the world the way Walt Disney did and they will also tell you, immediately, that Walt Disney was their hero.”

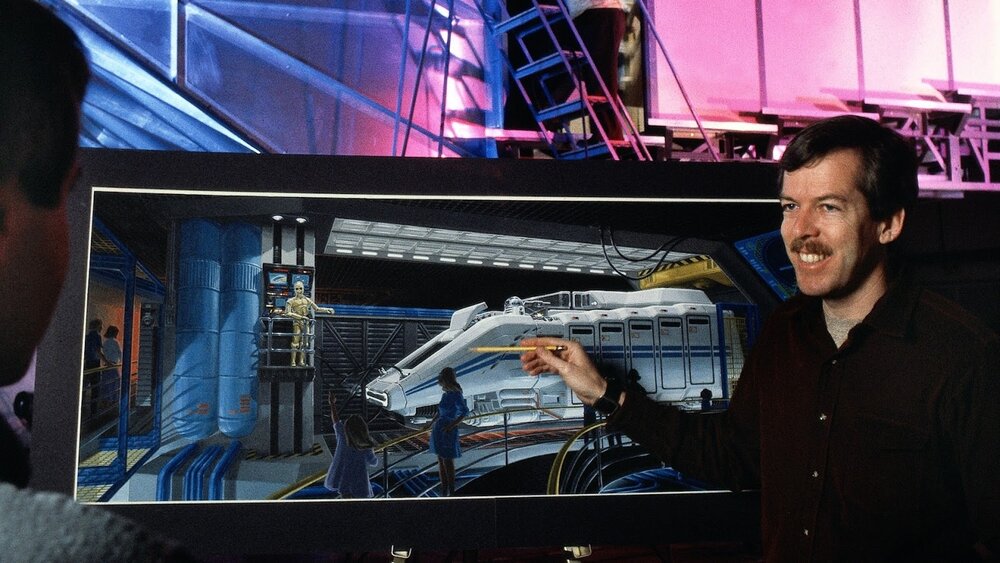

It was promising enough for a sit down. Baxter met Lucas at Miller’s California vineyard, not far from Skywalker Ranch, and the three talked. It was clear, before Eisner and Wells were even a possibility, that Star Wars was closer to a when than an if.

The first plan - a multiple-choice roller coaster - was dropped because of the massive real estate required. The back-up plan was already on the books and rolling around Baxter’s head.

Then came the change in management and, in September 1985, judgement day. To better understand the theme park business, Eisner and Wells asked Imagineers to pitch every idea they had, in-progress and otherwise. It was allegedly an opportunity to educate their new bosses, but Baxter and his colleagues didn’t see it that way. The unspoken objective was to justify their continued employment and prove they knew what guests wanted.

The judge was neither president nor CEO, however, but the latter’s 14-year-old son, Breck Eisner. If an idea passed his taste test, it was good enough for the grown-ups.

Baxter presented his Star Wars simulator. To nobody’s surprise, Breck loved it. To Baxter’s surprise, his dad loved it so much that he demanded another Lucas project open in Tomorrowland in the summer of 1986, a full year ahead of the so-called Star Tours.

Captain EO missed the mark by a month, but in mid-September of 1986, opened in Disney parks on both coasts. It was, in every way, of its time. A top-to-bottom Michael Jackson vanity project, co-starring all manner of gonzo creature, about saving the universe with a few good pop songs. With Lucas producing and buddy Francis Ford Coppola directing, the short film became, minute-for-minute, the most expensive film ever made at $1.76 million per.

The lasting popularity of Captain EO thereafter is up for debate, but the immediate effect was unmistakable. Disney found the pulse. Anyone still skeptical wouldn’t have to wait long for further proof.

On January 9th, 1987, Star Tours opened and stayed open for a sustained 60 hours just to handle the crowds. Baxter was right about motion simulators. Lucas was ecstatic about the partnership. So ecstatic, he just had to needle Spielberg, who’d been consulting in a similar fashion with Universal.

“You screwed up going with Universal,” he told his Indiana Jones cohort, “They could never do a Star Tours.”

Without realizing it, Lucas had poured gasoline on a fire. Spielberg believed in Universal’s theme park bonafides since its designers built a seven-ton King Kong in 1986. There had been talks soon after about a Back to the Future attraction, but no ride system seemed fit for it. After an early ride on Star Tours at his friendly rival’s request, Spielberg told Universal’s team to start messing with motion simulators. The promise of Back to the Future: The Ride was enough to resurrect the company’s plans for Universal Studios Florida.

For the first time since Star Wars and Close Encounters of the Third Kind, the old pals were going head-to-head, this time in Hollywood East.

In the Star Tours video press kit, Lucas fielded a question about what might be next for him and the Mouse with a trademark poker face. “I’m working on four or five other projects that will be coming out,” he said ambiguously enough, before dropping the magic words, “Some of them Indiana Jones rides.”

Alongside Star Tours, The Indiana Jones Epic Stunt Spectacular was intended to be part of the day-one line-up at the Disney-MGM Studios. That sort of rock-‘em-sock-‘em demonstration had been Universal’s stock in trade for decades, and the new Florida park would include updates of Hollywood’s Wild, Wild, Wild West Stunt Show and Miami Vice Action Spectacular.

The $20 million Epic aimed to beat them both in a single show, with more educational content and the largest movable stages in the world to boot.

The story goes that park guests are watching Raiders of the Lost Ark as it’s shot. But the jig is only up after a live recreation of that film’s iconic opening sequence. Once Harrison Ford, or rather his stunt double, is pancaked by the boulder, the film’s second unit comes out to applaud. The stunt double walks out, miraculously three-dimensional, and emphasizes just how heavy the ball is as two grips effortlessly roll it back into place. That spectacle and its resulting punchline set the tone before anyone says, “Action!”

Directed by Jerry Rees of The Brave Little Toaster and staged by actual Raiders stunt coordinator Glenn Randall, Jr., The Indiana Jones Epic Stunt Spectacular would prove an enduring hit with audiences, key word would.

Both of Lucas’s attractions overshot opening day by months, with Star Tours stretching into December. Instead of leaving the 2,150-seat amphitheater empty for the park’s first summer, Lucas and Eisner allowed guests to sit in on technical rehearsals until it was ready in August.

If the day was too hot or the viewer too antsy, they could also pay Indy a visit in The Great Movie Ride. Animatronics of Harrison Ford and John Rhys-Davies lifted, but never quite carried their prize out of a stunning recreation of the Well of Souls, accurate down to the C-3PO and R2-D2 hieroglyphics.

Comments

What a wonderful deep dive on the relationship between Lucas, Spielberg, Indiana Jones, and the Disney parks, and the impact they've had. Indiana Jones has captured the hearts and imaginations of millions, and I hope that Disney will continue to create ways for the fans to participate in his adventures. Loved this article!