Haunting divisions

After Walt’s death in 1966, some – even inside the company – wondered if the Walt Disney Company could continue at all. After all, a generation of Americans had grown up with Walt Disney, seeing his face on television, hearing of him in the news, and watching his name flash before their favorite motion pictures.

To those folks, “Disney” was a man’s name first, and a company second. Many wondered if it might feel disingenuous to see a movie carrying his name, but without his direction. What was the Walt Disney Company without Walt Disney?

Similarly, the Disney parks went through a tumultuous period of upset without Walt’s direction. What would become of The Haunted Mansion, for example? Its gleaming white plantation house exterior was ready in 1963, but at the time of Walt’s death, the interior of the ride was still directionless.

And after his death, competing ideas of what the Mansion should contain were pitted against one another.

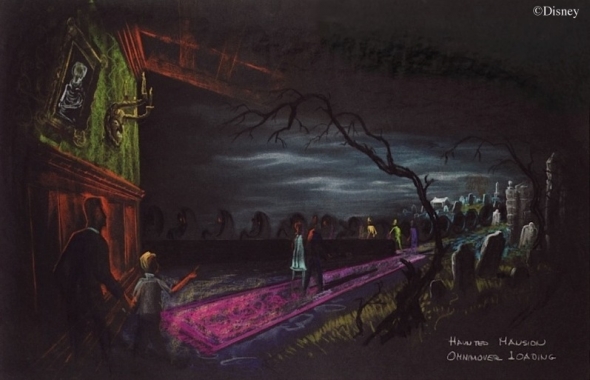

In one corner stood Claude Coats, famed artist and designer whose credits stretched back to Walt’s earliest cartoon shorts, through Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs, and up through the opening of Disneyland and beyond. Coats’ idea for the Haunted Mansion was that it ought to be a chilling, haunting, surreal trip through a ride packed with unfathomable special effects. His storytelling style also necessitated that the ride be free from plot or narrative and very visceral. His famed "Limbo" boarding (concept art above) set the metaphysical, ominous tone.

Across the way stood Marc Davis, equally renowned and celebrated artist and Imagineer whose credits included many famed animated characters and the audio-animatronic figures on Jungle Cruise, Tiki Room, and Carousel of Progress. Davis’ school of thought – as evidenced in his later work on Pirates of the Caribbean – was a character-driven, plot-focused attraction filled with Animatronics and light-hearted gags. The Hatbox Ghost, the Hitchhiking Ghosts, and the cemetery characters were all results of Davis' more lighthearted view of what the Mansion should be.

Ultimately, the Haunted Mansion that ended up opening in 1969 was a clever combination of the style of both men – a haunting, moody, ominous opening act from Coats, and a rousing, character-driven, singsong, gag-filled second act from Davis that, in many regards, resembles the atmosphere of Pirates. These two men are their particular, complimentary styles will play into Discovery Bay soon.

A new decade

In 1970 – just a year after the Haunted Mansion opened – a new Imagineer joined the team. Fresh out of college, the young man was Tony Baxter. He’d worked at Disneyland part time throughout high school and college, working his way up from an ice cream scoop position to a ride operator on the park’s Submarine Voyage. For a final project in a college design course, Baxter had designed a Mary Poppins ride for Disneyland. A few informal connections got the plans to veteran Imagineers like Coats and Davis, and after a tour and a change of schools, Baxter was in.

His first project with Imagineering well encapsulates Disney’s position in the 1970s. He was sent directly to Orlando alongside Claude Coats to oversee the artistic set design for Magic Kingdom’s version of the Submarine Voyage. But this new Floridian version would be stylized after a famous Jules Verne's novel (and Disney's equally renowned 1959 film adaptation). You can read the in-depth story in our standalone entry, Lost Legends: 20,000 Leagues Under the Sea. While the ride was very similar to Disneyland's original, it was placed in Magic Kingdom's Fantasyland and given the Jules Verne overlay to fit stylistically. (For Baxter's part, he went from operating Disneyland's part time in 1969 to being the artistic designer of Magic Kingdom's the very next year).

Once Magic Kingdom opened in 1971, Baxter returned to California and to an Imagineering group alight with ideas. The 1970s would be a time of tremendous and unprecedented growth for Imagineering, and the decade is responsible for many classically loved attractions today.

Baxter shines

With Imagineering gearing up for a decade of immense change and extraordinary attractions, Baxter was invaluable. He was, put simply, the first of a new generation of Imagineering. Straight out of school and no doubt filled with fresh optimism, he fell under the wing of Claude Coats, who would become his enduring mentor alongside John Hench and Marc Davis.

It had to have been a beneficial relationship for both. For one thing, this new generation of young, upstart Imagineers had never worked alongside Walt Disney. Indeed, Tony was eight years old when Disneyland opened, while most of his senior colleagues had been the ones responsible for its opening. However, Tony also had his own upper hand – he had grown up with Disneyland. He had visited as a guest. He had worked in the park’s day-to-day operations in a way that the senior Imagineers could never have. His unique perspective would be an asset.

And even right off the bat, the plans he had would change everything. Indeed, Disney was facing a very serious problem in Florida and California, and Baxter would develop the plans to fix it…

Thunder Mesa

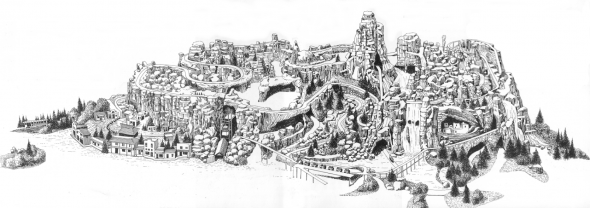

Magic Kingdom opened in 1971 with a large plot of land left open in its Frontierland in the northwest corner of the park. Marc Davis (the Imagineer behind Pirates of the Caribbean and the character-driven second act of Haunted Mansion) had elaborate plans to build an attraction complex there. The massive Thunder Mesa complex would've contained multiple attractions wrapping around and throughout the desert setting.

Thunder Mesa's E-Ticket, though, would be the other inhabitant of Possibilityland: Western River Expedition – a character-heavy dark ride that would’ve been Magic Kingdom’s answer to Pirates of the Caribbean, themed to the Old West and populated with heroic cowboys. An epic floating dark ride through cinematic Western landscapes, Davis designed the unique and stunning attraction intentionally, since Imagineers believed that pirates would bore Floridian visitors. After all, pirates were a reality in the nearby Gulf and the stuff of local lore, not something exotic and mysterious.

Once guests made it to the new park, it did not escape public notice that Magic Kingdom had taken many of the best elements of Disneyland and supersized them… except Pirates of the Caribbean. Guests allegedly asked routinely where the Pirates ride was and when it would open.

In response, Disney began work on an answer, hastily constructing a shortened version of Disneyland’s Pirates of Caribbean at the Magic Kingdom. The turnaround was quick, and Florida's Pirates opened in 1972. But with Pirates, Magic Kingdom would not need Western River Expedition, so the Thunder Mesa attraction complex was axed. But the idea of the Western River Expedition lived on and would inspire a new E-ticket for Frontierland just when it needed it most...

Reactions

Disneyland has always been an exemplary example of design principles at work – an escapist reality, just detailed enough to feel inhabitable, but with impossible fantasy behind each faux doorway. It’s a place to engage the masses by allowing them to descend into worlds they’ve always dreamed of.

But that dream hasn’t always been the same.

When Disney fans think of “Adventureland,” it’s irrevocably tied to visions of deep jungles, misty rivers, and exotic animals. But… why? Why, of all the “adventures” out there was this single genre selected to embody it all? Put simply, Disneyland’s themed environments are reactions. They’re answers to the popular culture at the time they were built. Disneyland’s Adventureland is a jungle because, in the early 1950s, public interest peaked in the “exotic” jungles of Africa, safaris, and wild life.

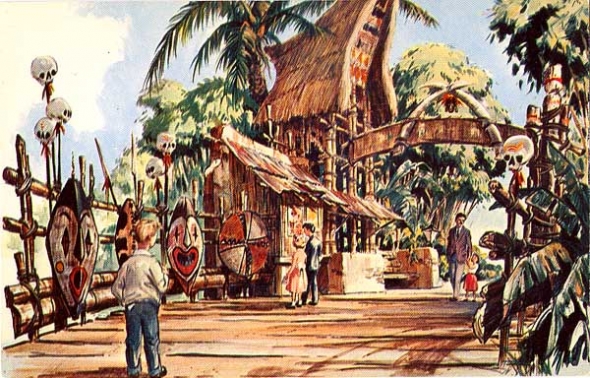

Then, by the turn of the decade, things had changed. With Hawaii’s entry into the United States in 1959, the craze of Tiki culture swept the country and suddenly the Polynesian mysticism and romance became the ideal “adventure.” Tiki bars opened in cities around the U.S., Gilligan's Island hit the airwaves, and Adventureland’s first expansion followed suit as “adventure” changed definitions.

When you think about it, it happened again in the 1990s. With the once-"exotic" jungles of the undeveloped world now accessible instantly via the Internet, Adventureland shifted again. Now tinged with fantasy, the whole land has a new narrative - a 1930s lost Indian delta expedition overseen by Indiana Jones - the new American ideal of "adventure."

We know that the same happened to Tomorrowland (1967) and would happen to Fantasyland (1983) as each land responded to the shifting perceptions of their respective eras.

But one area of the park was still in need of updating.

The Frontierland problem

Walt’s last contribution to Disneyland was New Orleans Square with its two E-tickets: Pirates of the Caribbean (1967) and the Haunted Mansion (1969). Originally intended to be an expansion of Frontierland, the New Orleans corner eventually annexed itself entirely into a new land.

Which was all well and good, except that the old Frontierland was feeling very lifeless in comparison.

For one thing, the land’s only attraction was a Walt original: the Mine Train Thru Nature’s Wonderland. While it was exceptional for the era it was built in, its time was coming to an end as visitor numbers dropped and interested faded.

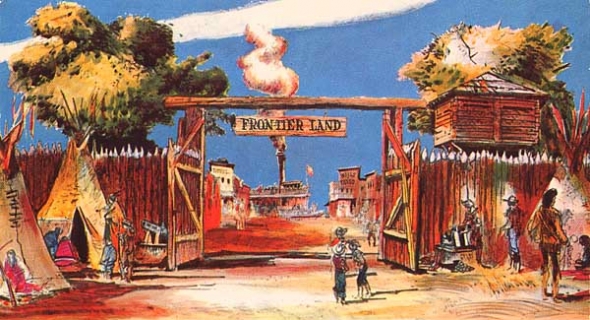

But secondly, Frontierland had simply lost its luster in the public eye. During the park’s initial planning, the concept of the American frontier was at the forefront of popular culture. Davy Crockett and The Lone Ranger had re-ignited the television screen; “Cowboys and Indians” was the choice backyard game for young children and it seemed that the West would forever be a romantic ideal on par with the jungles of Adventureland or the storybook villages of Fantasyland. But by 1970, it wasn’t. The public’s interest in the Old West had dried up (and arguably hasn’t returned since, despite some earnest efforts).

It's one thing to incorporate society's current ideas of "adventure" into Adventureland, but what can be done to a Frontierland when the concept of the American frontier has run its course?

Barely 25 (but with Claude Coats, Marc Davis, and the best of the senior Imagineers to guide him), Tony Baxter was faced with the seemingly improbable task of making Frontierland relevant to a society that couldn’t care less about cowboys and Indians.

On the next page, we’ll step into Tony Baxter’s brilliant and beloved Discovery Bay, his idea for the expansion Frontierland needed. We think that you’ll agree upon reading that most every attraction he designed would’ve been an instant classic. But let’s enter Discovery Bay together.

Comments

It would be a fantastic land to be added to the Disney Parks. The film "TomorrowLand" was an excellent film though I feel it had it's release dampened by its competition in the box office. It had Steampunk and Jules Verne elements tied with a theme of timeless optimism and development. Discoveryland could be just what the world needs, even if it doesn't know it.

I know that Claude Coats was his mentor, but this is the first I've heard of Marc acting as such. In those days, Davis people and Coats people stayed in separate camps.

Coats was definitely his mentor more than anyone else out the gate, but Baxter benefited from both schools of thought, it seems. When you think about it, most any successful and "classic" Disney ride has elements of both designers (and obviously many more), and Baxter seemed to have registered that and incorporated a balance between them into his creative process!

Sometimes, Tony's projects leaned more toward Davis' style! Think of his Phantom Manor, which more or less conceded the Haunted Mansion debate to Davis' character-driven favor. Other times, he took Davis'-style concepts and made them a bit more abstract, as in Paris' Pirates. But altogether I think he simply learned that their two styles are complimentary, not mutually exclusive. Which has been a tremendous benefit for us as guests!

Bravo, Brian!

This was such a well researched and thought out article, fascinating to read. It gave me a much deeper appreciation of Tony Baxter.

Looking forward to more of your work.

Thanks Chris! On my profile you'll find quite a bit more that I've written on lost concepts and closed attractions that you might find interesting! But I'm a huge fan of Tony Baxter and it's hard not to be. He's responsible for so many of the modern attractions we love, and for so many more that fans beg for.