The Golden Age of Automata

Automata, or automatons, really came into their own during the Industrial Revolution. It was a time of massive, quick-moving changes in all phases of manufacturing and production. Toymakers eagerly adapted such new inventions as steam power and a plethora of machine tools. In addition, the economic boom and falling prices meant that more of the population had more disposable income to spend on novelties.

However, the true Golden Age of Automata came just after the close of the Industrial Revolution, during the years 1860 through 1910. In France, hundreds of small family-owned businesses exported thousands of automatons, particularly singing birds, across the globe. These pieces marked a return to the whimsy of the ancient automatons, coupled with the lifelike realism honed just before and during the Industrial Revolution. Many of these pieces draw extremely high prices on the secondhand market today.

Walt Disney

Walt was born during the Golden Age of Automata, on December 5, 1901. However, there is nothing in the historical records to suggest that he ever came across one of these elaborate pieces during his early life. Automatons were not cheap, and the Disney family was decidedly working class. Walt was only four when the family moved from Chicago to a farm in Marceline, Missouri. Although by all accounts his childhood in Marceline was idyllic in many ways, it did not include such luxuries as expensive imported toys.

After the end of the Golden Age in 1910, public interest in automatons waned. The business went on, creating some highlights such as Sparko, the robot Elektro’s robotic dog, that could bark, beg, and sit. The pair appeared at the 1939 World’s Fair. In general, though, the rapid succession of World War I, the Great Depression, and World War II created economic and sociological changes that made the automaton somewhat passé.

Meanwhile, Walt Disney thrived. After a stint as a cartoonist for his school newspaper, he attempted to enlist in the army at age 16, but was denied due to his age. He then drove an ambulance in France for the Red Cross before taking an art studio position in 1919. After a couple of tries at running his own studio in Kansas City, Walt pooled resources with his brother Roy to open a cartoon studio in Hollywood in 1923. One thing led to another, culminating in Walt’s first Academy Award in 1932 for the creation of Mickey Mouse.

Although there were certainly trials and tribulations, and Walt repeatedly had to put his own livelihood on the line for a new project, his talent and contributions were undeniable. His first feature length animated film, Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs, proved his star power upon its 1937 release. During World War II, most of the studio’s resources went into creating military training films, but after the war, Disney returned to what it did best, churning out animation while also veering into full-length dramatic films that blended animation with live action.

Walt discovers the automaton

In the late 1940s or early 1950s (sources disagree as to the exact year), Walt took his family on vacation to either New Orleans or Europe (sources also disagree as to the location). In an antiques shop, he discovered a mechanical singing bird created in the 1850s. As the story goes, he was so intrigued that he bought the bird, brought it back to his studio, and directed his team to disassemble it to see how it worked.

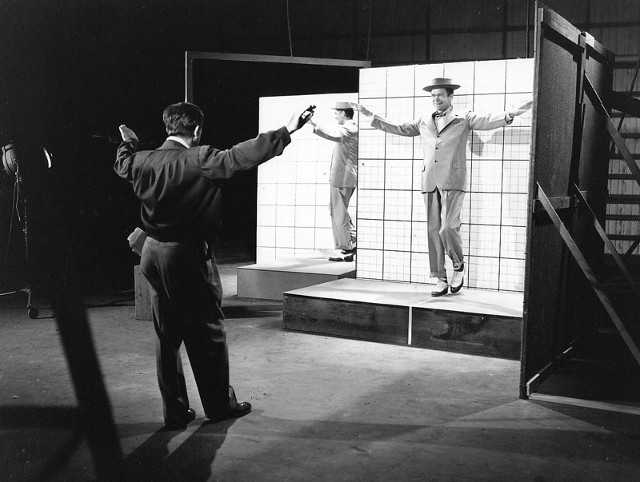

Walt was highly interested in the possibilities that the little bird represented, and he was curious to see if a human character could be done. In 1951, a team headed by machinist Roger Broggie and sculptor Wathel Rogers was given the sizeable task of creating a nine inch tall human figure that could dance, move, and even talk, dubbed Project Little Man. They brought in actor Buddy Ebsen to provide vaudevillian dance routines for the Little Man to perform, but quickly realized the limitations of the cam and lever technology. Instead, Broggie theorized, a life-sized figure would provide enough room for integrated hidden systems with a more sophisticated blend of electronics and pneumatics. Walt was intrigued, but also wrapped up in his latest and most unlikely project—the development of a full theme park. Project Little Man was put on hold.

Disneyland

As Walt told the story, while on one of his weekly outings with his two daughters, Sharon and Diane, at a local amusement park, he decided that there must be a better way. He sat on a bench while they went on rides, and he looked around at all the other parents doing the same thing. He also noticed how dirty and ragged the park seemed. He envisioned a family-oriented park with high standards of cleanliness and maintenance, along with rides that all generations could enjoy together.

Originally planned for a small plot of land across from the studio, the Disneyland dream grew and evolved into something much larger. The park opened on a 160 acre plot in Anaheim, California, on July 17, 1955. Yet the park held only a handful of moving automatons (remember, the “audio animatronic” had not yet been invented), such as the animals of the Jungle Cruise and the barely moving figures of the original Peter Pan’s Flight.

Enchanted Tiki Room

Walt continued to grow, tweak, and "plus" his park, putting a great deal of effort into his tinkering. In particular, he kept returning to the idea of creating a next generation automaton that would synchronize lifelike movements with speech, or at least some sort of vocalization. Finally, in 1963, he realized that dream when he opened the Enchanted Tiki Room. Light years ahead of his own automatons, themselves a vast improvement on what had come before, the birds of the Tiki Room were the first true audio animatronics.

For the first time, more than 200 birds, tikis, and flowers were able to perform together in a tightly choreographed show that repeated throughout the day. The secret was in electromechanics. The entire show was recorded on magnetic tape. Without getting too technical, specific sounds on the tape triggered a set of electrical reactions within the figures that resulted in the opening or closing of pneumatic valves that created movement. A vast hidden room filled floor to ceiling with computers was required to run the magnetic tape system. The show still operates nearly identically today, albeit with some technological enhancements.

The show was so groundbreaking, so revolutionary, that people literally stopped in their tracks to marvel at the barker bird outside. Visitors eagerly lined up to pay 75 cents for the experience, a princely sum in those days. It is safe to say that the Tiki Birds were an immediate hit, and Walt was heady with excitement.

Add new comment