A world in miniature

Miniature trains were not the only small-scale replicas of real-world objects that captured Walt’s imagination. At the same time he was collecting new elements for his office railroad, he was also purchasing all manner of other miniatures, including furniture, coaches, farm machinery and figurines.

This went beyond a hobby – Walt’s aim was to create an entire turn-of-the-century village, inspired by his former home town of Marceline. This could then be displayed in large cases all over the country, as part of an exhibit known as “Disneylandia”. In the pursuit of this plan, Walt moved layout artist Ken Anderson onto his personal payroll and set him up in a private office. “I want you to draw 24 scenes of life in an old Western town,” he instructed Anderson. “Then I’ll carve the figures and make the scenes in miniature.” Anderson recalls in Gabler's book that Walt would often bring in a “whole sack full” of items after disappearing for days at a time.

The first scene that Walt constructed was based on a set from So Dear to My Heart, and was dubbed Granny Kincaid’s cabin. It featured recreations of a spinning wheel, a guitar, a washbowl and pitcher and numerous other household items. Walt took a hands-on approach, creating the chairs by bending wood in his family’s pressure cooker. A narration was recorded by Beulah Bondi, who played Granny in the movie.

As Walt’s ambitions for the project grew, he realised that Anderson’s scenes – which included a blacksmith reading a newspaper, a general store and a group of gossiping women – were too complex for him to produce on his own. He recruited a sculptor named Christodoro to help. He also recognised that, without movement, the scenes would be dull to engage an audience.

In 1949, Walt bought a mechanical, caged bird during a visit to New Orleans. The bird was capable of moving its tail and beak, and also tweeted out a song. Impressed, Walt ordered technician Wathel Rogers to “take this apart and find out how it works.” After dismantling the bird, Rogers found that its mechanisms consisted of clockworks and a double bellows.

Having completed the cabin, Walt set to work on a second, more ambitious scene – one that would incorporate the learning from the dissection of the bird. This one would be set in a frontier music hall, complete with an entertainer performing a dance. He hired dancer Buddy Ebsen to perform on camera, capturing his movements on 35mm film to enabling Roger Broggie and his technical team to analyse them in detail. Walt’s challenge to the machine shop crew was to animate a nine-inch figure created by Christodoro with the same movements. They achieved this using a system of cables and cams.

Although Walt initiated work on a second moving model, this time of a miniature barbershop quarter that could sing Sweet Adeline, it became clear that his idea for a traveling exhibit would never turn a profit. The Granny Kincaid scene was unveiled at the Festival of California Living at the Pan-Pacific Auditorium in Los Angeles in November 1952, but by this stage Walt had bigger ideas to occupy his time.

“It’s going to be clean!”

Decades later, the influence of Walt’s loves of trains and miniatures on the creation of Disney’s theme park empire is clear for all to see. At the time, however, few may have guessed where they would lead. The third hobby that played a role in the development of his vision should (and indeed did, in some cases) have tipped off those around him as to his intentions. Quite simply, Walt Disney was enthralled by amusement parks.

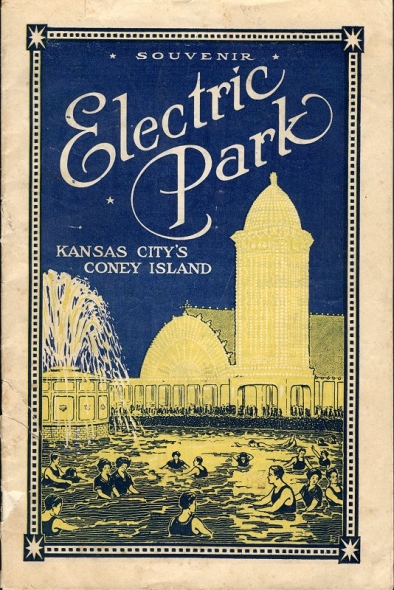

As a child growing up in Kansas City, Walt had frequently visited Electric Park, which was located just 15 blocks from the family home. He continued these visits in adulthood. On one visit in 1920 with Rudy Ising, an employee of his fledgling Laugh-O-Gram animation studio, he reputedly declared: “One of these days I’m going to build an amusement park.” He then added: “And it’s going to be clean!” At the time, amusement parks were renowned for being dirty, unkempt places staffed by surly employees.

After he became a father, Walt regularly took his daughters, Diane and Sharon, to Griffith Park in Los Angeles on Saturdays. In a 1963 interview, he recalled: “I’d take them to the merry-go-round, sit on a bench, you know, eating peanuts. I felt there should be something built where the parents and the children could have fun together.”

At the grand premiere for Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs in 1937, Walt had a dwarfs’ cottage erected outside the Carthay Circle Theater. Animator Wilfried Jackson recalls that, impressed by the reaction to the cottage, Walt broached the idea of building an amusement park.

By this stage, Walt was frequently receiving letters from fans of his productions asking to come and visit the Disney studio. Often, they would ask to “meet” characters such as Mickey Mouse and Donald Duck themselves. Other studios, including Universal Pictures, offered tours of their facilities, and Walt considered taking a similar approach. However, Disney’s focus on animation would be a problem - he did not believe that watching “a bunch of guys bending over drawings” would appeal.

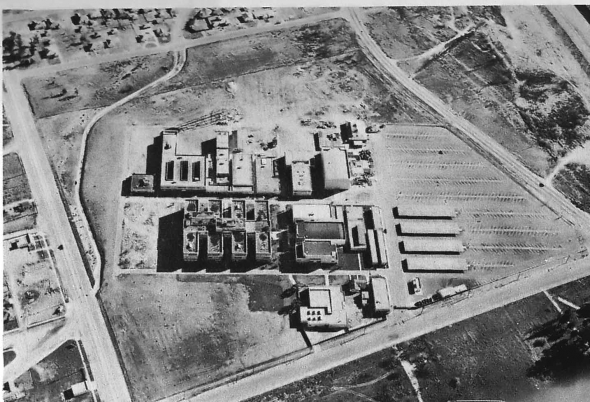

Flush with the success of Snow White, Disney concocted plans to build a new studio on a 51-acre plot in Burbank. Even before the studio opened, Walt hit upon the idea of building an amusement park on part of the property to satisfy the urges of those wishing to visit the Disney studios. In 1939 – prior to the opening of the Burbank studios – he summoned brothers Bob and Bill Jones from Disney’s Character Model Department to his office, and asked them to come up with some initial ideas for a park to be located on a small plot on the studio site.

The pair toured amusement parks in the area, and visited Walt to present their initial ideas six weeks later. Their proposed park was designed to meet his desire to offer something for the whole family, in a clean, wholesome environment. It would consist of a Pinocchio-inspired Bavarian village, and would host attractions include a traditional merry-go-round and a train ride around the perimeter of the park. The highlight would be a dark ride through the mine from Snow White, complete with animated characters.

The outbreak of the war in Europe and the resulting pressures on the Disney studio meant that Walt’s amusement park dream was put on hold. However, it continued to gestate in his mind. On a 1940 visit to New York with director Ben Sharpsteen, he discussed plans to install a small park across the street from the studio, between Riverside Drive and the Los Angeles River. Later, animator John Hench would spot Walt pacing around the parking lot in the new studio, seemingly measuring out the boundaries of the park.

Some accounts of Walt Disney’s life portray him as dreamer, only able to achieve to his great feats thanks to the practical, financially-savvy brain of the less creative Roy. While it is true that Roy played a vital role in supporting his younger sibling’s plans, Walt was anything but scatter-brained. He researched and planned his various projects in meticulous detail, and the amusement park was no exception. Walt himself visited dozens of amusement parks, including those in Coney Island in New York and Knott’s Berry Farm in Buena Park, California. He was not a passive visitor, grilling the operators, staff and even visitors with questions during every visit. As he began to form a team to develop the amusement park, he tasked its members with doing the same, aiming to learn about every aspect of the parks’ operations.

While he was toying with miniatures – a relatively low-cost, low-risk way of testing his concepts for a visitor attraction – Walt was actively plotting the installation of a narrow-gauge railway at the studio. Prior to his departure for the Chicago Railroad Fair in August 1948, he had already tasked fellow enthusiast Casey Jones with finding a locomotive for the railway, which would wind its way around a “village”.

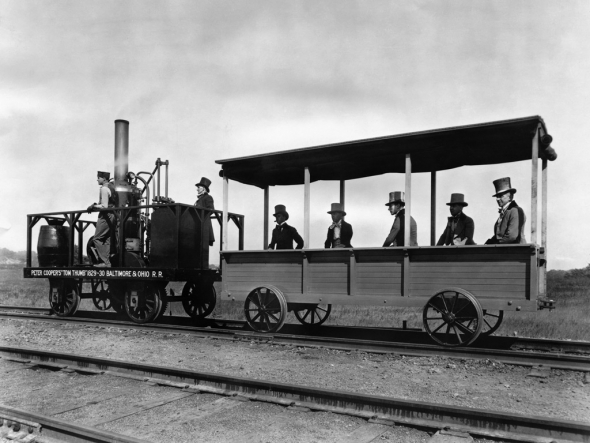

The trip to the Railroad Fair was the catalyst for moving the project forward. The fair itself, with its collection of trains, themed areas and costumed staff, provided inspiration enough. Walt and Kimball explored a replica of New Orleans’ French Quarter, a generic national park (complete with a geyser that erupted every 15 minutes) and an Indian Village. The president of the Chicago Museum of Science and Industry, Lenox Lohr, even allowed them backstage during the spectacular Wheels a Rolling pageant, offering them the chance to run famous locomotives like the Lafayette, the John Bull and the Tom Thumb.

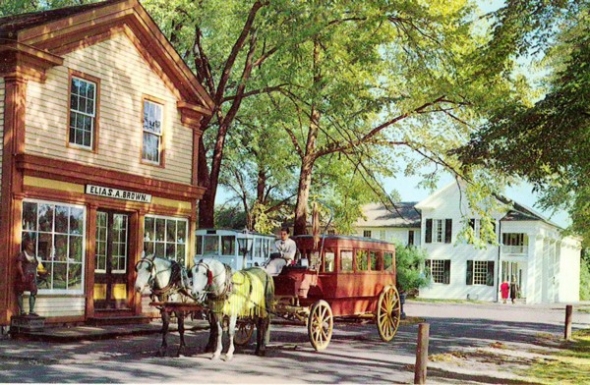

However, it was a side trip to the Henry Ford Museum in Dearborn, Michigan that really set Walt’s mind racing. Adjacent to the museum sat Greenfield Village, which hosted a collection of historical buildings that had been moved and reconstructed on the site. Ford’s collection included Thomas Edison’s laboratory and the Wright Brothers’ bicycle shop. There were also rides, including a 1913 Dentzel merry-go-round and a stern-wheeler riverboat. To travel around the property, visitors could board a working steam train.

Greenfield Village was exactly the type of attraction that Walt envisioned setting up at the studios. In itself, visiting a car manufacturing plant might be relatively uninteresting. But the museum and village gave guests something unique and entertaining to do. On top of that, it was clean, well-maintained and manned by friendly staff. It validated Walt’s concept for an amusement park to sit alongside his animation studios. Kimball recalled that Walt talked about the proposed park constantly during the trip.

Just days after arriving home, on August 31, Walt dictated a memo to production designer Dick Kelsey in which he outlined his vision for the park, which would be situated on an 11-acre triangle of land on Riverside Drive. At this early stage, it was to be known as Mickey Mouse Park. In addition to the train, Walt set out to acquire other attractions, sending the head of Disney’s foreign operations, Jack Cutting, to scout for merry-go-rounds in Europe.

By October 1948, the plans were on hold. Walt wrote to a Santa Fe executive with whom he had discussed the park at the fair, saying: “To tell the truth, I have been so involved in production matters since I got back that I haven’t given any further thought to my project."

It wasn’t until summer 1951 that another excursion provided the impetus to get the project back into development. Walt toured Europe with Lillian, and visited the famous Tivoli Gardens in Copenhagen. He was impressed by the cleanliness of the park, the beauty of the surroundings, the quality of dining on offer and the pleasant disposition of the employees. It was a world away from what he had experienced at Coney Island. “Now this is what an amusement place should be,” he declared to his wife.

Walt asked Harper Goff, an art director at the studio and fellow railway fanatic, to produce sketches of the park. These were expanded upon with drawings by architect John Cowles, and subsequently by further sketches from animator Don DaGradi. It is from these drawings and sketches, which were ultimately presented to the Burbank Parks and Recreation Board, that we can get an impression of the experience that would have been on offer to guests at Mickey Mouse Park.

Comments

Great bit of history!

Did you also know that there was a ski resort that Walt had invested in and was considering becoming a Disney destination ski resort? It is in the High Sierras. Near the town of Truckee California. It is called Sugar Bowl. It has Mount Disney and two lifts one called the Disney Express! It is also where he got his inspiration for "The Art of Skiing" with our Friend Goofy.

Actually, there were two possible ski resorts: Mineral King, south of Sequoia National Park, and Independence Lake, near Truckee. Disney helped design the Winter Olympics venue in Squaw Valley, California in 1960 and the other two projects followed.