Flaws in the system

While FastPass still exists at several Disney theme parks, the company eventually sought a replacement with MyMagic+. The explanation for this billion dollar enterprise is that there are numerous issues with FastPass. From the first days of its implementation, clever/deceitful consumers uncovered flaws in the system.

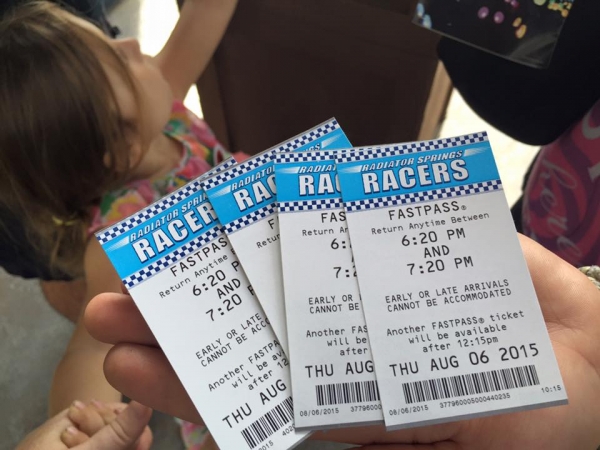

At the start, FastPass printouts didn’t include significant identifiers. There were date stamps on the tickets, but they were in fine print relative to the larger text of the return-time windows. People started realizing that they could pick up discarded FastPass printouts to use during future visits. This may sound unbelievable today, but it was a serious issue at the time.

The cause for such flaws was understandable. Disney Imagineers tried to build the user-friendliest system possible, which meant printout minimalism. The FastPass acquisition process involved two phases. The first step was getting the FastPass printout as documented above. The second step involved returning at the designated time to enjoy the attraction. At this point, the FastPass holder would show their ticket to the Cast Member manning the Priority Pass Entrance. The employee would wave them through to the shorter line queue. When the park guest reached the ride itself, a different Cast Member would ask for the ticket and then provide the guest with access to the attraction.

Despite the legendary diligence of Disney employees, few people holding FastPass tickets were ever turned away at the start. Corporate policy dictated that employees never tell guests no. If someone showed up too early for their FastPass window, the Cast Member politely advised them to return later when the ticket would become valid. If the guest showed up well after the expiration of the window, say 8 p.m. for a FastPass that expired at noon, the vast majority of employees honored it anyway at the company’s request.

Handing a Cast Member an expired ticket seems like something an employee should catch, but few did. In the early days, they received training saying not to scrutinize the tickets carefully beyond the start of the FastPass window. Someone showing up at 11:15 a.m. in the example above would receive notification to return at noon, but that was the only type of refusal encouraged. So, someone who had a FastPass from a previous day could use it as if it were new, an exploit that shameless guests abused.

There were other flaws as well. Enterprising guests discovered another system flaw when they inserted expired tickets and annual passes into the FastPass kiosks. Due to poor error checking, the original versions of these machines failed to recognize outdated tickets. So, they dutifully spit out valid FastPasses. People who knew about this error could have the run of Disney theme parks, riding to their heart’s content. Disney always targeted eight to nine rides as the intended number for guests during a quality day at one of their theme parks. With minimal effort, people employing this exploit could wind up with 10+ FastPasses.

Another known issue was the printout itself. The FastPass wasn’t exactly the dollar bill with regards to counterfeiting prevention techniques. Clever malcontents recognized that they could create their own versions of the printouts at home. There were even downloadable Make Your Own FastPass kits available online. The most enterprising of these folks started selling their counterfeit offerings on eBay. Guests would buy them online and then show up for a day of maximum riding at a Disney theme park. Suffice to say that when Disney grew wise to this trick, a lot of people wound up experiencing disappointing days at the Happiest Place on Earth before presumably returning home to leave a lot of negative feedback for the shady sellers.

Keeping it honest and boosting awareness

Over time, Disney evolved the FastPass concept to encourage greater use while discouraging dishonesty. They started changing the nature of the printouts to reflect a time stamp to avoid future-date cheating. They also altered the dissemination of FastPass printouts by changing the way the machine cut them. The updated kiosks cut the tickets differently, creating a perforation that was more difficult for people to mimic during counterfeiting attempts. They also updated the software to determine the validity of park tickets prior to authorizing the FastPass. Eventually, Disney even trained their Cast Members to reject FastPasses beyond the return time window, which caused a fair share of disgruntled customers.

The cheaters were the smaller concern to Disney. Sure, the company didn’t like that some guests were ripping off the system, but it didn’t bother them anywhere near as much as the sheer volume of park guests who ignored FastPass entirely. Disney observers chronicled this oddity for years. Guests would stand in line directly under FastPass signs that displayed return-times to note that if they acquired such a ticket, they would get to enjoy the attraction sooner. People stood in the long lines anyway. Disney must have felt like they were engaged in a food fight with someone on a hunger strike.

The company tried to boost FastPass awareness in numerous ways. They added central kiosks that allowed guests to acquire FastPass tickets for rides throughout the parks. The idea was that the walking might have discouraged people from participating. They added informative display signs to show how advantageous FastPass usage was relative to standing in line.

Disney even altered the fundamentals of the program to allow people to carry multiple FastPasses at once. Rather than receive a new one after the old one expired, the company added a new element to the printout in 2002. A second time listed on the ticket signified the moment when a person could acquire a different FastPass, even if they had not used the prior one. In this manner, theme park guests could finally hold multiple valid FastPasses simultaneously.

Savvy visitors maximized their days at the Happiest Place on Earth by developing intricate strategies to attain the most FastPasses possible. They learned that some later attractions weren’t added to the original distribution system. Popular rides such as Roger Rabbit’s Toon Town at Disneyland offered FastPasses that didn’t count against the waiting window for the attractions on the main system. The same was true of Disney’s California Adventure’s nighttime show, World of Color.

Traffic and the burning platform

Image: Disney

Disney began the development of My Magic+ and its offshoot, FastPass+, due to lingering issues with the original FastPass system. Ostensibly created to reduce wait-times, the first version of FastPass never truly achieved that goal. There was no hard data to reflect that guests were spending more money at Disney theme parks, either. The decidedly mixed results were a source of continued frustration for the company.

To understand the issue, think about how FastPass should work. Over time, Disney executives have collated extensive data about attraction behavior. They understand that Omnimover rides provide an easily calculated rate for ride occupancy since they move at the same speed all day. Keeping rides such as The Haunted Mansion full of guests shouldn’t require much strategy, but there’s still a science to the process. It should service a certain number of guests each hour and, thereby, each day. That traffic should be relatively static.

Image: Disney

Image: Disney

Through the FastPass system, Disney should have the ability to drive guest behavior by providing FastPasses at set increments. Rather than offering a guesstimate about wait-time, the company should theoretically stabilize traffic throughout the day via this system. The only catch is that people have to use it. Disney theme parks were stuck in a precarious situation wherein not enough people used FastPass technology, while too many of the ones who did abused it.

There was also a second, much more dramatic problem. Disney Imagineers are notoriously stagnant in the best possible way. They see themselves as the keeper of the flame with regards to Walt Disney’s legacy. They would rather change too little than change too much. That’s why so much of each park has remained consistent relative to the way you remember them from your childhood. Many of the changes made are seamless ones that enhance your guest experience without altering the purity of your memories. That’s a wonderful development style that has worked for over half a century. It’s also what makes Disney the gold standard in the theme park industry.

Something changed that no Imagineer could have anticipated, though. You’re using it right now. The Internet represents landmark change in the way humanity interacts. It offers historic means of communication while providing novel new forms of entertainment. Disney theme parks once faced relatively little competition when it came to how people wanted to spend their free time. As the Happiest Place on Earth, it had an easy sales pitch. That was true until it discovered the proverbial Burning Platform.

You may remember this concept from your business class. It’s a theme based on a real incident from 1988 when a supervisor working on an oil rig woke up to discover that his habitat was on fire. Most of his co-workers died in the blaze, and he faced a literal life-or-death decision himself. Trapped in the middle of nowhere, he could remain on the platform and burn alive or he could alternately jump 15 stories to the waters below. The leap would probably kill him and, if not, he would freeze to death in the water within minutes. He chose to jump, noting during a television interview that he chose probable death over certain death.

Even as it stood as the most popular theme park enterprise in the world, Disney executives believed that the company stood on the proverbial Burning Platform in the social media era. They feared that newly available distractions would disrupt their business model in the same manner as the Internet had negated the need for print media and physical mail. Whether this belief was founded in reality or extreme paranoia is up for debate. Either way, the people running Disney experienced a compelling urge to address the inertia within their company’s theme parks.

Comments

Nice history of the Fastpass system. However, you keep referring to Walt Disney World as the "Happiest Place on Earth." That phrase actually refers to Disneyland in California, which still employs paper Fastpasses. Disney World is referred to as the "Most Magical Place on Earth" and employs MyMagic+.