Have you ever wondered how Disney creates those somewhat creepy, incredibly lifelike figures that are so prevalent at its theme parks? From Captain Jack Sparrow in Pirates of the Caribbean to Mr. Potato Head at Toy Story Midway Mania, Disney wouldn’t be the same without these realistic depictions of humans and animals, known as audio animatronics.

Of course, you will find similar figures, with different levels of realism, all over the place, from other theme parks to pizza chains, and even toys. These moving figures are a huge part of our everyday world. If you were born after the mid-1960s, you might not be able to imagine a world without them. Yet, at the 1964 World’s Fair, intelligent adults genuinely believed that Great Moments With Mr. Lincoln featured a live actor, as a robot that lifelike was simply unimaginable!

Here, we will pull back the curtain to take you inside the world of audio animatronics, from their ancient predecessors through the possibilities of tomorrow. We will look at the vital role Walt Disney played in creating modern audio animatronics, examine how the theme park wars honed their design, and explore the evolution of their inner workings through more than 50 years of technological advancements.

Ancient automatons

The term “audio animatronics” was coined by Walt Disney in the mid-1960s to define a specific type of electromechanical figure capable of lifelike, synchronized movement and sound. Although animatronics are in heavy use by many companies today, the phrase “audio animatronics” is actually trademarked by Disney.

Although Walt might have invented the audio animatronic, he did not invent the automaton. Moving figures of people and animals have been documented since the days of ancient Greece. Famous automaton inventors include, but are in no way limited to, King Solomon, ancient Chinese artificer Yan Shi, Islamic inventor Al-Jazari, and Renaissance artists Giovanni Fontana and Leonardo da Vinci.

The clockwork monk

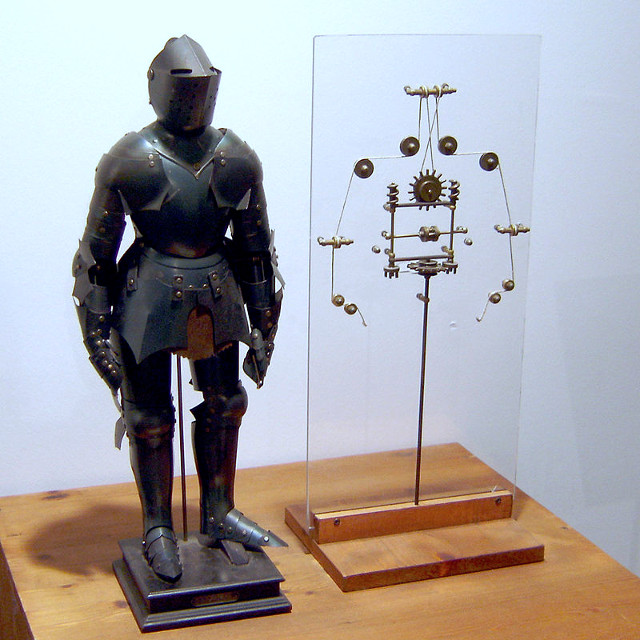

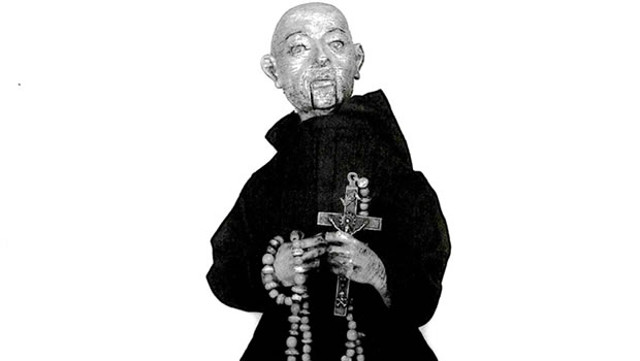

The Smithsonian Institution’s collection holds one of the oldest automatons still in working order, the clockwork monk, believed to have been created in Spain during the 1560s. Although its origins are murky, the clockwork monk is generally attributed to Juanelo Turriano, Emperor Charles V’s mechanician. As the story goes, the emperor’s son, King Phillip II, prayed by the bedside of his gravely ill son. He struck a bargain with God: a miracle for a miracle. If his son recovered, Phillip would create an earthly miracle. The boy survived, and Phillip arranged for the creation of this most unusual penitent icon.

Not a children’s toy, nor a fantastic piece of whimsy, the clockwork monk is a remarkably somber piece that strikes a deep emotional chord with all who witness it, even in the jaded 21st century. It is a remarkable piece of 16th century engineering, and unusual for its time in that each piece of the figure performs fully independent yet perfectly choreographed movements (as seen in the video below).

The monk stands approximately 15 inches high. Comprised of wood and iron, it is driven by a key-wound spring. Hidden clockworks turn its body, move its head side to side, raise its cross and rosary in the left hand, beat its chest with the right hand, position its eyes to look at the cross as it rises, and cause its sandal-shod feet to walk as rollers hidden in its robes propel it forward in a square pattern. Its mouth opens and closes as if reciting its prayers, and the systems even interact with each other as the monk lifts the cross to its lips and gives it a kiss.

The clockwork monk has been X-rayed and extensively studied since its 1977 arrival at the Smithsonian. Detailed drawings are freely available online. Yet the monk still stands apart as a true testament to the combined power of faith and human engineering.

Descartes and the Industrial Revolution

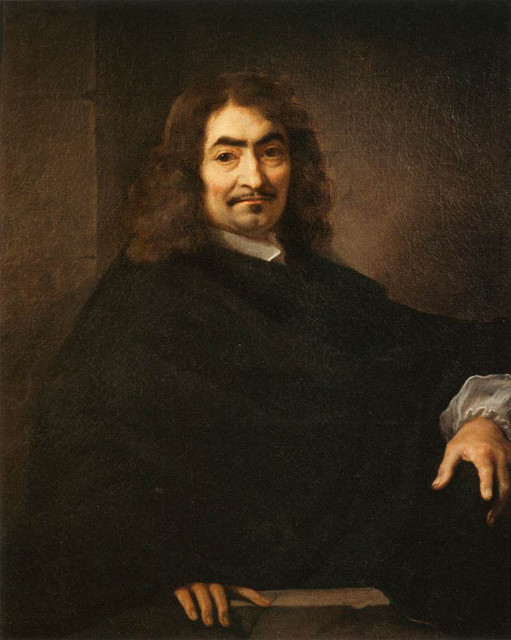

For most of history, automatons served purposes ranging from whimsy to religious iconography. They were toys for the wealthy and reverent pieces for the religious. They were not, however, considered part of the common workaday world. In the 17th century, philosopher and scientist Rene Descartes changed that view while simultaneously setting the stage for the Industrial Revolution that occurred a century later.

At that time, the Renaissance was coming to an end. A cultural reawakening after the darkness of the Middle Ages, the Renaissance was a time of art, literature, religion, and the development of the scientific method. In the waning years of the Renaissance, men who could combine nature with religion, and science with philosophy, were much heralded for their talents and revolutionary, forward-thinking ideals.

Rene Descartes was just that sort of man. Responsible for the foundation of analytical geometry, the Cartesian coordinate system, and infinitesimal calculus, he was also the father of rationalism and, indeed, all of modern Western philosophy. He was the first to describe philosophy as a system of thought that encompasses all branches of knowledge, to cast ethics as a science, and to develop a methodological system for testing and proving hypotheses.

What does all of this have to do with audio animatronics? Descartes was also the first to describe the living body as a machine. He suggested that bones, muscles, and other biological materials could just as easily be replaced by pistons, cams, and cogs. While this was part of a larger argument concerning the duality of the body and mind, in which he described the mind/soul as nonmaterial and existing outside the realm of biology, society was ready to grab hold of the “man as machine” concept. A new era of mechanical toys was born.

Harnessing the power of mechanical energy as derived from Newton’s Laws of Motion, mechanical toys were not new in Descartes’ day. However, the focus began to shift from whimsy to realism, creating startlingly lifelike (for their time) reproductions of animals and men.

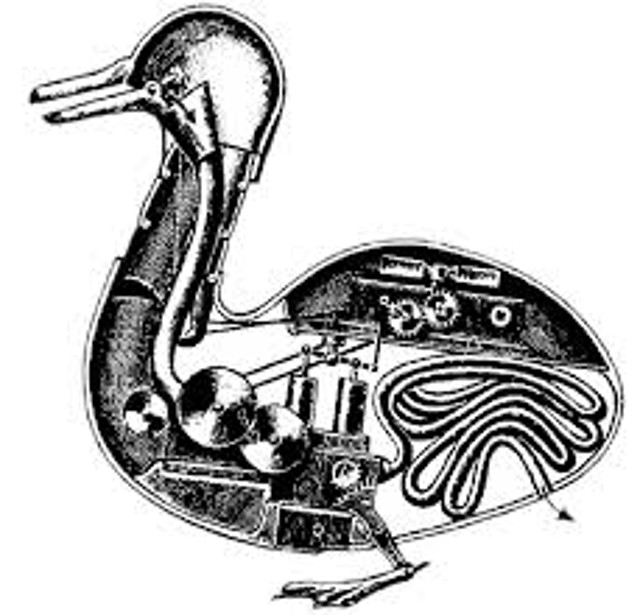

Perhaps one of the most realistic was the Digesting Duck, created by French inventor Jacques de Vaucanson in 1739. Powered by a complicated system of flexible rubber tubing, levers, and cams, the gilded copper duck could flap its wings and splash in water. But its most impressive feat was its ability to eat from a person’s hand and then deposit dung pellets onto a silver platter. Although crude and even gross by today’s standards, the duck drew rave reviews in the royal courts of Europe, even prompting philosopher Voltaire to suggest that a trip to France would be incomplete without seeing its marvel.

The automaton revolution went global, with toymakers in Japan and China eagerly embracing the craze. As the 1700s drew to a close, many of the automaton models became prototypes for the massive machines that marked the beginning of the Industrial Revolution.

Add new comment